-

20 de February de 2018

Retrospective Section //2017//

The Retrospective presents a great name of world cinema with a retrospective and a deep reflection about the author’s work and career.

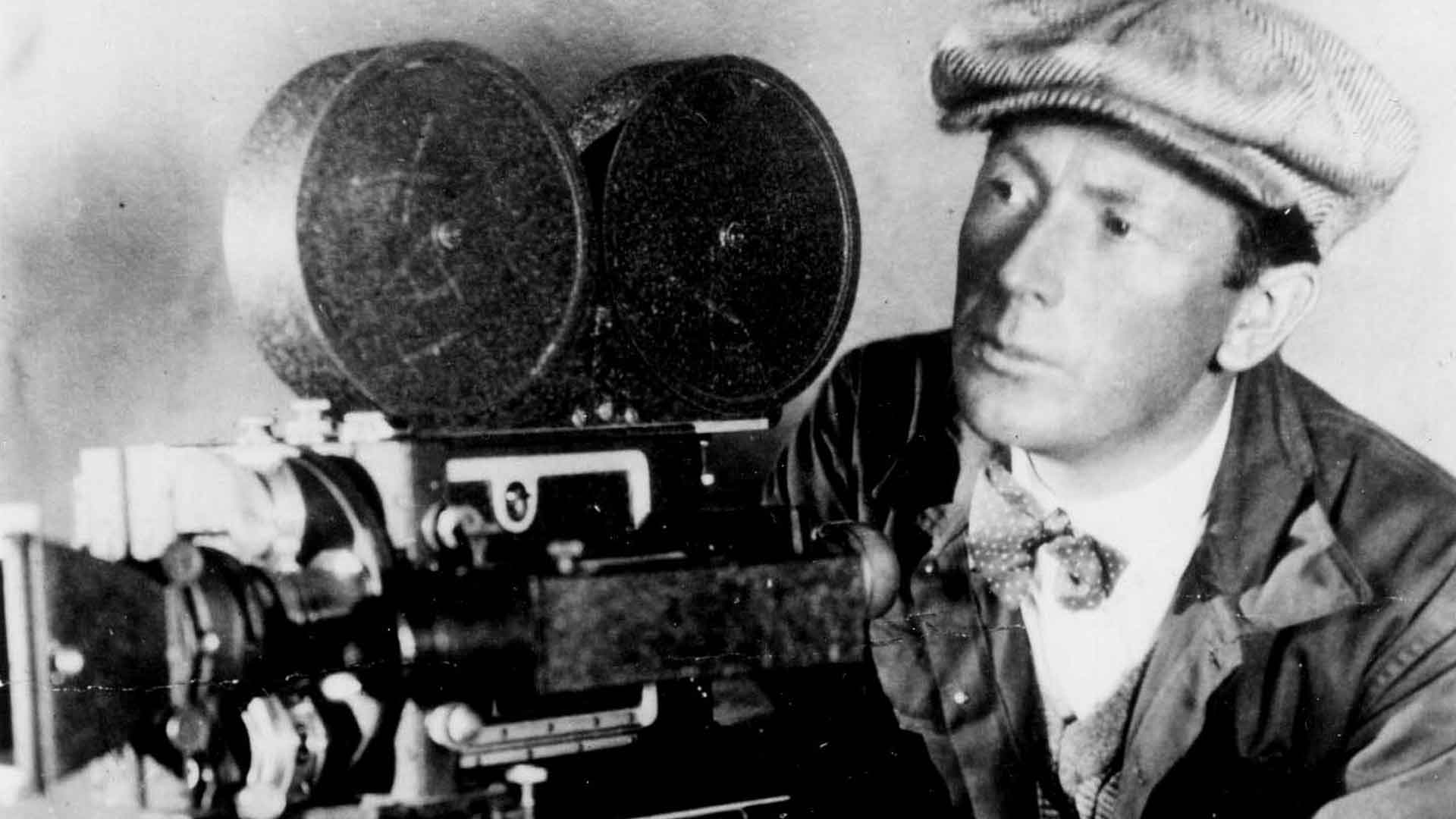

About F.W. Murnau

Aaron Cutler

February 14, 2018

The idea for last year’s Olhar Retrospective of Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau’s films (https://woocommerce-460761-1467366.cloudwaysapps.com/2017/2017/olhar-retrospectivo-f-w-murnau/) first came to me when I read about the Munich Film Museum’s new restoration of the great Expressionist and Romantic director’s earliest surviving film, 1921’s The Dark Road (information about which can be found in English here – http://www.giornatedelcinemamuto.it/en/der-gang-in-die-nacht/ – and here – http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2016/11/06/murnau-before-nosferatu/). But perhaps it was really first born on the night of Sunday, April 4th, 2010, when I went on my first date with a Brazilian woman named Mariana Shellard to see a 7:40 P.M. screening of Murnau’s film Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927) at the theater Film Forum in my then-home city of New York. Now, more than seven years after moving to live with her in São Paulo, Murnau and Brazil remain linked in my mind.

The retrospective offered audiences restored DCP copies of 10 out of Murnau’s 12 surviving films (during his short life, he made a total of 21), including The Dark Road and Sunrise, as well as eight other films provided by a wonderful preservation center for older German and Weimar Republic cinema called the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation. The word “restoration”, in practical terms, refers to the physical repairing of damaged elements, which thanks to archivists such as Luciano Berriatúa (https://woocommerce-460761-1467366.cloudwaysapps.com/2017/2017/o-cinema-de-murnau-por-luciano-berriatua/) has been carried out with great care and respect for Murnau’s work. And restoration, appropriately, is the central theme of Murnau’s films, in which psychologically damaged individuals find ways to survive in the world through imagination and hope.

It was incredibly rewarding to see people line up to watch well-known masterworks like The Last Laugh (1924) and Tabu: A Story of the South Seas (1931), as well as lesser-known but equally great films such as Phantom (1922). The sold-out crowds at screenings of this cinematic innovator’s films served as a strong rebuke against the idea that experimental cinema cannot attract audiences. I am grateful to everyone who in some way contributed to the retrospective, including the participants in the “Murnau’s Legacy” seminar (https://woocommerce-460761-1467366.cloudwaysapps.com/2018/en/news/page/2/) that occurred during the festival, as well as all the critics that wrote about the films with care and sympathy.

If I could recommend one Murnau film to this post’s readers, it would be a film that we did not show: City Girl (1930), a tremendously warm, gentle, and generous work that Murnau made as an unofficial sequel to Aurora. We did not screen it because, although 35mm prints of the film do circulate, it has not yet received the DCP restoration that it deserves. In the meantime, the film can be watched here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oT1kZYjOi4M

And, if I could express one regret about the retrospective, it was that I as the series curator did not consult other people more for ideas about how to best present the films. This year’s Olhar Retrospective will thus be different from last year’s in a crucial way. Although the films cannot be revealed yet, I am proud to say that I will be working on the retrospective with Carla Italiano, who is new to the features selection committee this year after working with shorts in 2017. The opportunity that we all have to benefit from this extraordinary person’s work is both a privilege and a very great gift.